Image processing with Juicy Pixels and Repa

First published: June 7, 2016

by Mark Karpov

Tested with:

- Resolver: LTS Haskell 5.16 (ghc-7.10.3)

- Libraries: JuicyPixels-3.2.7 repa-3.4.0.2

In this tutorial we will learn how to efficiently generate, transform, and process images in Haskell. This sort of task is interesting to solve in a pure functional language, because it's parallel in nature — processing of images requires performing identical manipulations on many pieces of data (pixels). On the other hand, such manipulation cannot be performed efficiently with the help of familiar primitives for parallel Haskell computing (the Eval monad, evaluation strategies, and the Par monad with IVars) because these rely on laziness which works with boxed data, while for efficient processing of large arrays of numbers it's desirable to use unboxed data.

This tutorial assumes basic knowledge of Haskell, as after reading Learn You a Haskell for Great Good or similar books. You don't need to know much more than that, but some unfamiliar terms will show up unavoidably, so if you don't yet understand underlying concepts, it's OK, you still can use the libraries, get the work done, and return to the subtle topics later (I give links for further reading in this article every time some mysterious Haskell concept shows up).

Available libraries

There are a number of libraries for image processing available in the Haskell ecosystem. Some make use of external tools written in other languages, others are written entirely in Haskell. First, I would like to list libraries that are conventionally used for image processing and manipulation with short descriptions, because we don't have space to cover them all in this tutorial.

JuicyPixelsis a lightweight library written in Haskell that allows to load and save images in various formats. It can be used to convert, generate, and process images. Pixels are packed in unboxed storable vector — no automatic parallel execution, but quite fast for simple tasks. We cover the library in the tutorial.repastands for “REgular PArallel arrays” and is not specifically tied to image processing, but it's the standard choice when you want to perform calculations on a large collection of numeric data in parallel in Haskell. We cover how to use it for image processing in this tutorial.fridayis a powerful and relatively new package that allows to manipulate images and has a good collection of operations already coded for you (like edge detection, cropping, filtering, etc.). Its principles of operation are very similar to those of Repa, so after reading this tutorial you should have good intuition of how to code withfridaytoo. To load images,friday-devilis usually used, but note that it requires external DevIL library.glossdescribes itself as “Painless 2D vector graphics, animations and simulations”. Indeed, it can do more than just image editing and there are some nice demos to get you started creating animations and simulations. Note thatglossuses OpenGL under the hood.

We will use the lightweight library JuicyPixels for reading and writing image files, and repa for efficient processing of numeric data.

Juicy Pixels

JuicyPixels is useful on its own if your task does not require parallel computations. Simple things like badge or identicon generation can be done sequentially (the overhead of scheduling parallel execution for small amounts of data can even make sequential execution preferable) and the JuicyPixels API makes them ridiculously simple.

Types and data structures used in Juicy Pixels

If we quickly glance through the Codec.Picture module, its types and functions look really straightforward. The basic type in the module is Image, which is parametrized by pixel type:

data Image a = Image

{ -- | Width of the image in pixels.

imageWidth :: {-# UNPACK #-} !Int

-- | Height of the image in pixels.

, imageHeight :: {-# UNPACK #-} !Int

-- | Image pixel data. To extract pixels at a given position

-- you should use the helper functions.

--

-- Internally pixel data is stored as consecutively packed

-- lines from top to bottom, scanned from left to right

-- within individual lines, from first to last color

-- component within each pixel.

, imageData :: V.Vector (PixelBaseComponent a)

}The definition is simple and intuitive: we have the width and height of image and single vector that contains pixel data.

! before Int is called a “strictness annotation”. Haskell, being a lazy language (should I have said “the lazy language”?), does not normally evaluate fields inside of a data structure when data constructor itself is evaluated. When only the constructor is evaluated, data is said to be in “weak head normal form” for some obscure historical reason (fully evaluated data is said to be in “normal form”). The ! sign says: “Hey, we are all in one boat now, if you evaluate the constructor, evaluate me too”.

Here is how it works. Suppose we have this data type:

data MyData = MyData !Int IntOne Int has a strictness annotation while the other does not. Load the definition in GHCi and try for yourself:

λ> let d = MyData (1 + 2) (3 + 4)

λ> :sprint d -- :sprint shows what's evaluated and what's not, unevaluated

-- data is shown as underscore ‘_’

d = _ -- the whole thing is unevaluated

λ> d `seq` () -- seq guarantees that both its arguments will be evaluated

-- before it returns a value (which is equal to the second argument unless

-- the first argument is bottom)

()

λ> :sprint d

d = MyData 3 _ -- strictness annotation in actionBear with me because these things are important for understanding performance-related issues and design decisions of tools we are talking about.

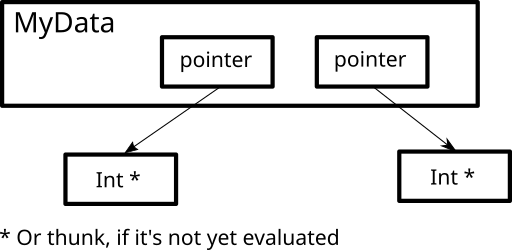

{-# UNPACK #-} is a different story. To make things lazy, Haskell by default represents everything as “boxed” data, that is, it stores a pointer to Int in MyData, not the Int itself:

Boxed data in Haskell

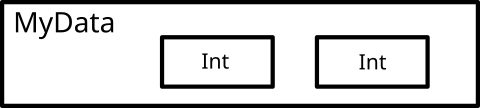

Thunk is a name for data that hasn't been evaluated yet. When the {-# UNPACK #-} pragma is used, data becomes part of parent structure:

Unboxed data in Haskell

To do something with the Ints inside, we don't need to de-reference the pointers, which makes things faster. Of course in this case we cannot retain high level of granularity with respect to lazy evaluation and we have to make unboxed data strict. Interestingly, GHC won't let you use {-# UNPACK #-} without strictness annotation saying that it's a parse error.

I explained this in detail because imageData is a Vector of pixels and this vector is unboxed and thus it's not possible to use Eval or Par to compute different parts of it in parallel. Also, the Vector of pixels is immutable so every time you change it, you create a new vector copying all the data because normal Haskell's mechanisms for sharing data work well only with boxed data. We will return to this when we start talking about Repa and will see how the problem is solved there.

To give the programmer a single image type that represents “just” an image, abstracted from its representation, Image is put into the DynamicImage wrapper:

data DynamicImage =

-- | A greyscale image.

ImageY8 (Image Pixel8)

-- | A greyscale image with 16bit components

| ImageY16 (Image Pixel16)

-- | A greyscale HDR image

| ImageYF (Image PixelF)

-- | An image in greyscale with an alpha channel.

| ImageYA8 (Image PixelYA8)

-- | An image in greyscale with alpha channel on 16 bits.

| ImageYA16 (Image PixelYA16)

-- | An image in true color.

| ImageRGB8 (Image PixelRGB8)

-- | An image in true color with 16bit depth.

| ImageRGB16 (Image PixelRGB16)

-- | An image with HDR pixels

| ImageRGBF (Image PixelRGBF)

-- | An image in true color and an alpha channel.

| ImageRGBA8 (Image PixelRGBA8)

-- | A true color image with alpha on 16 bits.

| ImageRGBA16 (Image PixelRGBA16)

-- | An image in the colorspace used by Jpeg images.

| ImageYCbCr8 (Image PixelYCbCr8)

-- | An image in the colorspace CMYK

| ImageCMYK8 (Image PixelCMYK8)

-- | An image in the colorspace CMYK and 16 bits precision

| ImageCMYK16 (Image PixelCMYK16)Its data constructors are an enumeration of images that correspond to supported pixel types. The result is that we can use the DynamicImage type without caring much about the concrete underlying representation.

Pixels in turn are just a collection of numeric components, for example:

data PixelRGB8 = PixelRGB8 {-# UNPACK #-} !Word8 -- Red

{-# UNPACK #-} !Word8 -- Green

{-# UNPACK #-} !Word8 -- Blue

deriving (Eq, Ord, Show)Many functions from Codec.Picture take or produce DynamicImage. As an example, look at readImage, savePngImage, saveBmpImage and others:

readImage :: FilePath -> IO (Either String DynamicImage)

saveBmpImage :: FilePath -> DynamicImage -> IO ()

saveJpgImage :: Int -> FilePath -> DynamicImage -> IO ()

savePngImage :: FilePath -> DynamicImage -> IO ()

saveTiffImage :: FilePath -> DynamicImage -> IO ()saveJpgImage takes an integer specifying desired quality as well. It's time to use this straightforward API for real work.

Format conversion program

We can put together an utility for image format conversion right now! Let's write a console program that takes the format of resulting image as the first argument and the path to source image as second argument. When the program is run, it converts image and saves it changing its extension appropriately.

Try to do it yourself first. Here are the imports and language extensions you will need:

{-# LANGUAGE RecordWildCards #-}

{-# LANGUAGE TypeOperators #-}

module Main (main) where

import Codec.Picture

import Control.Monad

import Control.Monad.ST

import Data.Array.Repa (Array, DIM1, DIM2, U, D, Z (..), (:.)(..), (!))

import System.Environment (getArgs)

import System.FilePath (replaceExtension)

import qualified Codec.Picture.Types as M

import qualified Data.Array.Repa as R -- for RepaOK, now we can compare our code:

data ImgFormat = Bmp | Jpg | Png | Tiff

main :: IO ()

main = do

[ext, path] <- getArgs

case fromExt ext of

Nothing -> putStrLn "Sorry, I don't know such format!"

Just fmt -> convertImg fmt path

convertImg

:: ImgFormat -- ^ Format of resulting image

-> FilePath -- ^ Where to get source image

-> IO ()

convertImg fmt path = do

eimg <- readImage path

case eimg of

Left err -> putStrLn ("Could not read image: " ++ err)

Right img ->

(case fmt of -- select saving function

Bmp -> saveBmpImage

Jpg -> saveJpgImage 100

Png -> savePngImage

Tiff -> saveTiffImage)

(replaceExtension path (toExt fmt)) -- replace file extension

img -- pass it 'DynamicImage' we've read

-- | Get file extension corresponding to known image format.

toExt :: ImgFormat -> String

toExt Bmp = "bmp"

toExt Jpg = "jpeg"

toExt Png = "png"

toExt Tiff = "tiff"

-- | Get image format corresponding to given extension or 'Nothing' if we

-- don't support that format.

fromExt :: String -> Maybe ImgFormat

fromExt "bmp" = Just Bmp

fromExt "jpeg" = Just Jpg

fromExt "png" = Just Png

fromExt "tiff" = Just Tiff

fromExt _ = NothingWe just built something useful with almost no effort, but what are our options if we wish to edit or generate an image?

Image rotation

For processing existing images the pixelMap function can be used:

pixelMap :: (Pixel a, Pixel b) => (a -> b) -> Image a -> Image bWith this function you can do something funny with colors, but let it be an exercise for the reader. How about operations that require random access to image's data? An example of such an operation is rotation.

Since type at the base of Image is a storable Vector (immutable, unboxed vector) and the standard technique for efficient vector generation is using its mutable variant, it's no surprise that JuicyPixels provides MutableImage type.

The basic workflow is the same as with vectors:

Allocate memory for a new mutable image (or create it from an immutable one).

Populate it with right values using mutability.

“Freeze” it and get your normal

Image.

Let's do it with JuicyPixels. We create new mutable images using one of the following functions:

-- | Create a mutable image with garbage as content. All data is

-- uninitialized.

newMutableImage :: (Pixel px, PrimMonad m)

=> Int -- Width

-> Int -- Height

-> m (MutableImage (PrimState m) px)

-- | Yield a mutable copy of an image by making a copy of it.

thawImage :: (Storable (PixelBaseComponent px), PrimMonad m)

=> Image px

-> m (MutableImage (PrimState m) px)Reading and writing are done via readPixel and writePixel (they have unsafe companions but we won't touch them here). freezeImage helps with freezing. Let's put it all together:

main :: IO ()

main = do

[path, path'] <- getArgs

eimg <- readImage path

case eimg of

Left err -> putStrLn ("Could not read image: " ++ err)

Right (ImageRGB8 img) ->

(savePngImage path' . ImageRGB8 . rotateImg) img

Right _ -> putStrLn "Unexpected pixel format"

rotateImg :: Image PixelRGB8 -> Image PixelRGB8

rotateImg img@Image {..} = runST $ do

mimg <- M.newMutableImage imageWidth imageHeight

let go x y

| x >= imageWidth = go 0 (y + 1)

| y >= imageHeight = M.unsafeFreezeImage mimg

| otherwise = do

writePixel mimg

(imageWidth - x - 1)

(imageHeight - y - 1)

(pixelAt img x y)

go (x + 1) y

go 0 0In rotateImg, we run a stateful computation inside the ST monad. You can think about ST monad as an “escapable” IO. References to mutable data cannot escape the ST monad, but pure data can. The ST monad is often used to write functions that manipulate mutable values as long as the result is referentially transparent.

We use unsafeFreezeImage instead of freezeImage to avoid unnecessary copying of data: unsafeFreezeImage re-uses memory occupied by its argument. Since after “freezing” we don't modify mimg, it's a safe thing to do.

As simple as that, we have rotated an image upside down:

Here is how our program performs (image-processing is the name of compiled executable):

$ image-processing before-rotation.png after-rotation.png +RTS -s

…

Total time 0.238s ( 0.142s elapsed)

…More information about subtleties of the vector package can be found here.

Image generation

Juicy Pixels provides a couple of useful functions to generate images:

generateImage :: Pixel a

=> (Int -> Int -> a) -- ^ Generating function, with x and y parameters

-> Int -- ^ Width in pixels

-> Int -- ^ Height in pixels

-> Image a

generateFoldImage :: Pixel a

=> (acc -> Int -> Int -> (acc, a)) -- ^ Function taking the state, x and y

-> acc -- ^ Initial state

-> Int -- ^ Width in pixels

-> Int -- ^ Height in pixels

-> (acc, Image a)

withImage :: (Pixel a, PrimMonad m)

=> Int -- ^ Image width

-> Int -- ^ Image height

-> (Int -> Int -> m a) -- ^ Generating function

-> m (Image a)If your image can be expressed as a function from coordinates to pixels, generateImage looks super-simple and straightforward. generateFoldImage allows to pass around an accumulator (i.e. you can have some sort of state). withImage is more interesting: it allows to use function that returns values inside instances of PrimMonad. PrimMonad is outside of scope of this tutorial, but if you are interested you can read about it here. Basically, PrimMonad means IO or ST and monad stacks with one of these monads at the bottom.

Let's generate an image using the generateImage function and save it as a PNG file. Here is my attempt:

main :: IO ()

main = do

[path] <- getArgs

savePngImage path generateImg

generateImg :: DynamicImage

generateImg = ImageRGB8 (generateImage originalFnc 1200 1200)

originalFnc :: Int -> Int -> PixelRGB8

originalFnc x y =

let (q, r) = x `quotRem` max 10 y

s = fromIntegral . min 0xff

in PixelRGB8 (s q) (s r) (s (q + r + 30))Juicy Pixels' generated image

Quite mysterious. Let's measure how our program performs.

$ image-processing my-image.png +RTS -s

…

Total time 0.197s ( 0.104s elapsed)

…Generation of image is not parallel, the library just repeatedly calls the provided function and builds the resulting image from returned results. The performance is not bad at all, but can we do better using multiple cores?

Repa

Here's where Repa comes into play. Operations on arrays performed in Repa are parallel by default if you compile your program with multi-thread support (the -threaded flag enables that) and run it with +RTS -N.

Do you remember the problem with large unboxed arrays? We certainly cannot afford the creation of a new big immutable array after each operation, so how can we avoid producing intermediate results?

Well, the answer is rather simple. Following the same approach with a function that takes coordinates as argument and returns a pixel, we can just make that single function more complex with help of primitives from functional programming like map but specialized for our purposes. Then we can call it to build the final result never creating intermediate ones.

The final “real” array is called “manifest array” in Repa's terminology, while the function that can be used to generate such real array is called “delayed array”. The trick of never building intermediate results is called “fusion”. This is a popular technique that is also used in the friday package and in the more mundane text.

Repa Arrays

Before we can start hacking with Repa, there is one more concept that needs to be explained: the Array type and its shape. Array r sh e type is parametrized over:

Representation

r: there are a few options available for that, but in this tutorial we will work only withU(unboxed vector, manifest array), andD(delayed array, function from indices to elements).Shape

sh: this describes how many dimensions your array has and sizes of these dimensions. Below I show how to work with shapes.Element type

e: in our case it will be(Pixel8, Pixel8, Pixel8)wherePixel8is just a synonym forWord8, i.e. a byte.

Shapes are constructed like this: you append dimensions to Z (zero-dimension shape) using :. type operator. The tricky part is that Z and :. live on both type level and term (value) level. For example:

Z :. 3 :. 3is shape of 3 × 3 matrix (Z :. Int :. Inton type level);Z :. 0 :. 0,Z :. 0 :. 1,Z :. 2 :. 2are examples of indices that can be used to access data in that matrix.

Positions are numbered from 0, and so Z :. 2 :. 2 is bottom right corner of such matrix. In reality, all elements are stored in a flat, one-dimensional vector and shapes just help access right elements. In fact we can re-shape a Repa array without modifying array itself:

λ> let arr = R.fromListUnboxed (Z :. 3 :. 3) [1..9] :: Array U DIM2 Int

-- the API is quite polymorphic, we need to give explicit type hints

λ> arr

AUnboxed ((Z :. 3) :. 3) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

λ> arr ! (Z :. 2 :. 2)

9

λ> arr ! (Z :. 0 :. 0)

1

λ> arr ! (Z :. 3 :. 3) -- hmm, what if…

*** Exception: ./Data/Vector/Generic.hs:235 ((!)): index out of bounds (12,9)

-- uh, oh

λ> R.reshape (Z :. 9) arr ! (Z :. 5 :: DIM1)

6Take a look at Simon Marlow's explanation of Repa shapes and indices for more information.

Bridge from Juicy Pixels to Repa

I will use two simple functions to convert between Juicy Pixels representation of pixels and Repa arrays:

type RGB8 = (Pixel8, Pixel8, Pixel8)

-- | Produce delayed Repa array from image with true color pixels.

fromImage :: Image PixelRGB8 -> Array D DIM2 RGB8

fromImage img@Image {..} =

R.fromFunction

(Z :. imageWidth :. imageHeight)

(\(Z :. x :. y) ->

let (PixelRGB8 r g b) = pixelAt img x y

in (r, g, b))

-- | Get image with true color pixels from manifest Repa array.

toImage :: Array U DIM2 RGB8 -> Image PixelRGB8

toImage a = generateImage gen width height

where

Z :. width :. height = R.extent a

gen x y =

let (r,g,b) = a ! (Z :. x :. y)

in PixelRGB8 r g bThe extent function returns the shape of given array. We represent images as two-dimensional matrix of three-tuples holding components of pixel's color: Array D DIM2 RGB8 and Array U DIM2 RGB8 where DIM2 is just built-in alias for Z :. Int :. Int.

Image rotation revisited

Let's re-write the code that rotates an image with Repa and see if it's worth it. To use Repa we need to compile our code with the following flags:

-Odph-rtsopts-threaded-fno-liberate-case-funfolding-use-threshold1000-funfolding-keeness-factor1000-fllvm-optlo-O3

Yes, all of this. Note the use of LLVM (enabled by -fllvm flag) which means you need to have it installed. When I tried to use version 3.8.0, I got the following:

You are using a new version of LLVM that hasn't been tested yet!

We will try though...

opt: /tmp/ghc13996_0/ghc_2.ll:7:6: error: unexpected type in metadata definition

!0 = metadata !{metadata !"top", i8* null}

^So I switched to version 3.5 which seems to work with Repa fine:

main :: IO ()

main = do

[path, path'] <- getArgs

eimg <- readImage path

case eimg of

Left err -> putStrLn ("Could not read image: " ++ err)

Right (ImageRGB8 img) -> do

computed <- (R.computeUnboxedP . rotateImgRepa . fromImage) img

(savePngImage path' . ImageRGB8 . toImage) computed

Right _ -> putStrLn "Unexpected pixel format"

rotateImgRepa :: R.Source r e => Array r DIM2 e -> Array D DIM2 e

rotateImgRepa g = R.backpermute e remap g

where

e@(Z :. width :. height) = R.extent g

remap (Z :. x :. y) = Z :. width - x - 1 :. height - y - 1

{-# INLINE remap #-}computeUnboxedP builds manifest unboxed arrays in parallel. It's a type-specialized version of the more general computeP function:

computeP :: (Load r1 sh e, Target r2 e, Source r2 e, Monad m)

=> Array r1 sh e -- ^ The delayed array to compute

-> m (Array r2 sh e) -- ^ Manifest array — resultAn interesting thing here is that computeP wants to live in a monad, any monad, why is that? The reason is that computeP can use an array that is produced with another computeP but only when it's already evaluated or else you get a run-time warning and slow code. If you keep all computeP and computeUnboxedP functions in the same monad, you are safe. So the type just helps avoid writing incorrect code (although it's still possible to use something like runIdentity . computeP). For sequential evaluation we have computeS, which may be a better choice for relatively small data-sets.

backpermute is “backwards permutation of an array's elements” and it's just the right tool for the job. Let's see what we get:

$ image-processing -- before-rotation.png after-rotation.png +RTS -s -N2

…

Total time 0.271s ( 0.156s elapsed)

…This seems to perform a bit worse, although both Juicy Pixel's and Repa's solutions have varying time of execution every time you run them. We could use a larger picture but then loading, saving, and transformation to JuicyPixels' representation would dominate processing time. We can use more cores though:

$ image-processing -- before-rotation.png after-rotation.png +RTS -s -N4

…

Total time 0.131s ( 0.073s elapsed)

…Doesn't look too bad.

Image generation revisited

Let's generate the same image with Repa:

main :: IO ()

main = do

[path] <- getArgs

img <- R.computeUnboxedP generateImgRepa

(savePngImage path . ImageRGB8 . toImage) img

generateImgRepa :: Array D DIM2 RGB8

generateImgRepa = R.fromFunction (Z :. 1200 :. 1200) originalFnc'

originalFnc' :: (Z :. Int :. Int) -> RGB8

originalFnc' (Z :. x :. y) =

let (q, r) = x `quotRem` max 3 y

s = fromIntegral . min 0xff

in (s q, s r, s (q + r + 30))Result with two cores is slower than plain Juicy Pixels version:

$ image-processing my-image.png +RTS -s -N2

…

Total time 0.276s ( 0.165s elapsed)

…Four cores improve the result a bit:

$ image-processing my-image.png +RTS -s -N4

…

Total time 0.152s ( 0.084s elapsed)

…Conclusion

Repa is great but watch out for where your bottleneck is. If you're doing a lot of IO in popular formats like JPEG or PNG, you will need Juicy Pixels and it may be worth it just to do the whole thing with Juicy Pixels. Repa has repa-io which can save in BMP (if that works for you), but for me it performed considerably worse than our toImage function in combination with JuicyPixels. There is also JuicyPixels-repa, but I got segfaults with it, no idea why.

Please feel free to comment on the tutorial, I'm not an expert of Repa programming, in fact this is one of my first experiences with the library, so maybe you can come up with an idea how to improve the tutorial or maybe make the code faster. Thanks for reading!

See also

List of resources that may be of interest:

Data parallel programming with Repa — Chapter 5 from Simon Marlow's “Parallel and Concurrent Programming in Haskell”, highly recommended reading.

JuicyPixelson Hackage.repaon Hackage.repa-algorithmson Hackage.repa-ioon Hackage.JuicyPixels-repaon Hackage.

What your fellow Haskellers did

Blackstar is a blackhole raytracer that uses Repa under the hood.

Curves is an interesting package that allows to draw curves, textures, and even text. It uses

JuicyPixels.FractalArt uses

JuicyPixelsto generate wallpappers with an interesting texture.

Thanks for reading this tutorial! If you have any feedback, please join the discussion below, or open issues and pull requests on GitHub.